How To Test Customer Demand For Your New Product

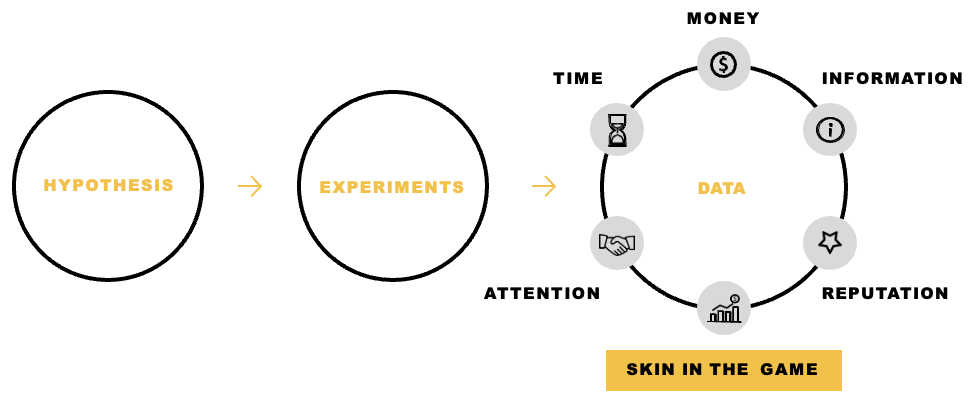

Product development is all about balancing risk and uncertainty over time. Highly relevant data from customers always wins out over opinions. Target customers who aren’t willing to put skin in the game are just spectators.

You may also enjoy these articles:

Introduction

To quantify customer demand for your big idea during the early stages of product development (think Problem-Solution Fit) you need to be able to capture evidence from your target customers.

The best evidence to capture from your target customers is some form of data that is quantifiable and measurable. Customer evidence may include money, time, personal information, or attention.

The best way to capture evidence from your target customers is through designing and executing highly targeted, fast, low-cost experiments.

These types of early-stage experiments use Marketing entry points to test initial levels of customer demand – for example, driving traffic to a landing page to measure behaviours and actions.

When a target customer is willing to provide evidence (I.e., Personal information) it equates to skin in the game. Skin in the game provides a level of interest and desire in your new product or service.

What doesn’t count as skin in the game are things like customer opinions, social media likes, shares or votes.

If your target customers aren’t willing to provide skin in the game, it’s a warning sign that your proposition isn’t resonating and, there’s more work to do to unlock customer value.

In this article we’ll discuss the following:

Why is evidence from customers important?

Not all data is created equally

The customer evidence leaderboard

Sequence experiments to decrease risk

Example - Nomad List - Testing a new online course offer

1. Why is customer evidence important?

Your objective is to gather data

During the early stages of new product development (before Product-Market Fit) you want to be aiming to validate your hypotheses as quickly and as cheaply as possible.

They key questions that you’re trying to answer are “Do I have a customer problem worth solving?” and “Are customers interested in my solution?”.

Note: some problems don’t matter and aren’t worth solving.

You need to be able to understand whether you’re on the right path or not … FAST!

The sooner, the better, so you don’t waste a whole lot of time and money pursuing an opportunity that is not valued by customers.

“Early on, your key objective is to qualify demand and interest in your big idea quickly at low-cost”

The best way to do this is to capture data and information from your target customers to qualify demand indicators and levels of customer interest.

The way that you gather data and facts from potential customers is designing and executing lightweight, fast, and low-cost experiments.

Measurable data and facts from customers are always valued higher than customer opinions or vanity metrics (I.e., social media likes)

Customer evidence decreases risk

Launching a new product or service is a high-stakes, high risk game.

I don’t need to tell you this, but this stuff is really hard.

Most new products fail. Most new product features have zero or negative value.

There are more losers than winners at this game.

You win when you can find a group of customers that value your product. You lose when you can’t.

“Loss comes with much more than not winning at the game, it comes with a loss of money, time and missed opportunities”

There’s significant downside spent pursuing the wrong idea.

If you’re going to play this game, you want to know that you can shift the odds more in your favour, increasing your odds of success.

The way that you shift the odds more in your favour is to get data from customers earlier.

Getting skin in the game from your target customers reduces risk. It is an early signal that customers are interested in your new product or service.

Target customers who are unwilling to put any skin in the game are just spectators.

Early-stage product development is all about balancing risk and confidence.

Skin in the game from your early adopter customers demonstrates interest, appeal, and commitment.

With appropriate levels of skin in the game, it warrants an incremental investment in time and money.

You can have more confidence your headed in the right direction.

Newsletter overload

There are email newsletters everywhere now. The market is saturated with a proliferation of email newsletters.

You’re not anyone unless you’ve got an email newsletter. #lifegoals

You name it, there’s a newsletter for it. Paid and free versions. Newsletter overload. Whoa!

I’m getting far more selective with the email newsletters that I sign up to nowadays. Otherwise, your inbox can just get drowned out in email newsletter clutter every day.

For me to sign up to a newsletter, it must provide differentiated and high calibre content. There’s so many newsletters competing for your attention that it needs to be good.

In saying that, there’s only a very small number of newsletters that I read regularly.

I sign up to newsletters that provide a different perspective, extend my point of view, and force me out of my echo chamber.

In this scenario, I like to “try before I buy” reviewing previous editions of the newsletter to ensure that the content is consistently high-grade.

Where there’s lots of value, I’m prepared to put skin in the game by handing over my email address.

Newsletters that just do average things, for average people, I don’t sign up. There’s no value.

2. Not all customer data is created equal

What data you should avoid

All forms of customer data should not be valued equally.

Data and facts from customers should always carry a higher weighting than customer opinions.

Data always beats opinions.

Customer opinions don’t count as skin in the game. There’s no commitment from the customer.

There’s no level of intent.

It’s dangerous to invest heavily in your new idea based on customer predictions of future events that may not occur.

What does not count as customer evidence:

Opinions

Expert opinions

Trend reports

Feedback from family and friends “that’s a great idea”

Surveys – asking people if they’d buy your product

Vanity metrics – social media likes

Customer polls or votes

Anyone will tell you your idea is good enough if you annoy them enough about it.

Compliments and opinions are the fool’s gold of customer learning – they’re shiny, distracting, and worthless.

Good quality customer evidence

Focus on collecting the following forms of data from customers:

Money – Ask customers to put down a pre-order payment or take an upfront credit card payment. For B2B purchases, ask the customer to sign a letter of intent.

Personal Information – Use an online form or modal to capture personal information. This could be an email address, phone number or home address.

Time – Ask customers to make a non-trivial time commitment (30mins+). This could be to attend a introductory meeting or briefing session about your product

Attention – Establish customer willingness to commit time to your product and solution without any incentives. This could be participating in a product research session

Reputation – Ask early adopter users to provide the contact details of friends and colleagues for a referral

Note: People stop lying to you when you ask them for money

3. Customer evidence leaderboard

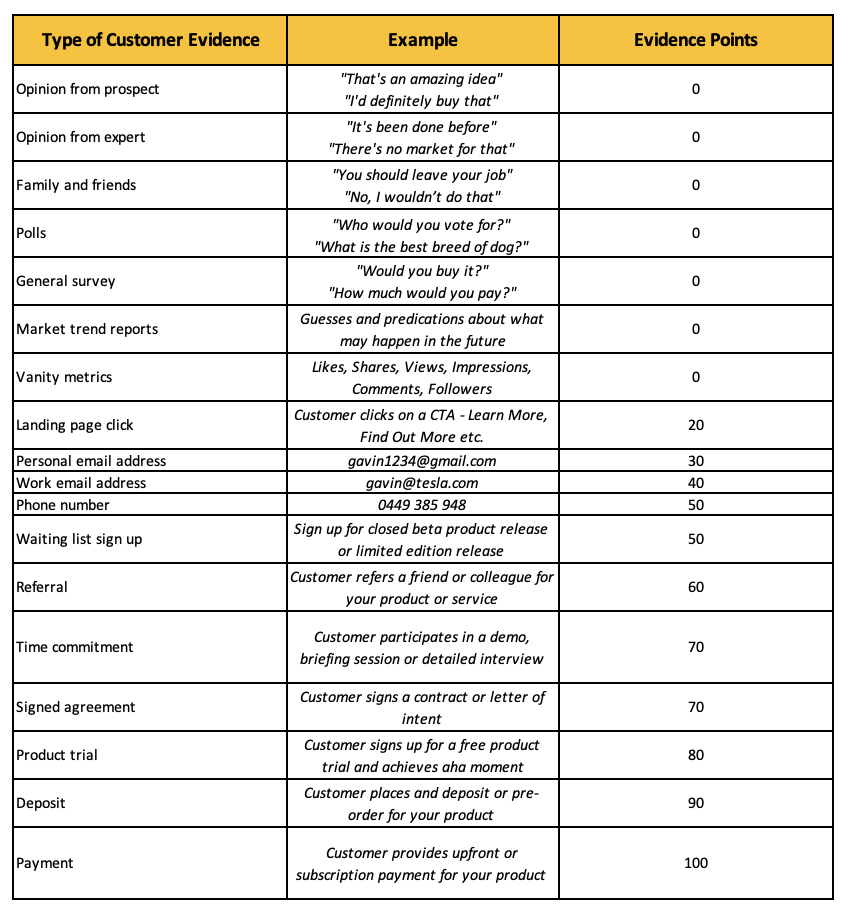

To ensure that you don’t fall into the trap of over-valuing the wrong types of data, use the customer evidence leaderboard to assess the quality of information that you’re gathering from customers.

Each type of data input is allocated a certain number of points.

The higher the evidence strength of the data point, the higher the number of points.

The leaderboard starts at 0 for low-quality evidence (opinions) increasing to a maximum score of 100 for the panacea of high-quality evidence, someone paying for your product.

This is a simple and fun way to objectively assess each of the different data inputs for early-stage product decision-making.

Adapted from Savoia

The bottom of the leaderboard

The bottom of the customer evidence leaderboard:

Customer opinions

Expert opinions

Feedback from family and friends

Polls

General “do you like my stuff” surveys

Market trend reports

Vanity metrics

There are certain types of customer data that should hold little weight when making important product decisions.

For example, opinions of any kind should hold little merit. Opinions are dangerous. This includes opinions from prospective customers, family, friends, or experts.

Asking customers about behaviours that they may or may not undertake in the future is fraught with danger. “Would you buy my product?” “How much would you pay for my product?”

Customers don’t know. We’re terribly bad at being able to accurately predict future events.

Likewise, it’s great to have encouragement and support from family and friends, however, these allies are not informed enough to understand if your idea is a good one, or not.

Opinions from experts must also be heeded with caution. Experts live in an echo chamber and suffer from extreme confirmation bias.

Experts typically only push a narrative that supports their beliefs or research. Review the work of experts, but you need to validate if what they’re saying is true.

Economists aren’t any better at predicting the future than you or I.

Market trend reports are like reading a fiction novel. It’s impossible to extrapolate out macro trends with any level of confidence or certainty. Interesting reading, that’s about it.

Finally, vanity metrics of any kind (Likes, shares, comments, views, followers etc.) also receive a score of 0.

These data points have no real value to your product or business. Anyone can mindlessly perform one of these actions.

It’s impossible to know what actionable steps you need to take to improve your product or service based on these data points and vanity metrics.

Moving up the leaderboard

The middle of the customer evidence leaderboard:

Clicks

Email addresses

Waiting list

Mobile phone number

Referrals

Time commitment

Now, we’re talking. This is where the rubber starts to hit the road.

These pieces of evidence are much more valuable than those at the bottom of the leaderboard, being indicative of initial levels of customer interest.

The weighting of these types of evidence strength rightly deserves a higher score.

Customers guard their time, personal information, and reputation closely. If they’re willing to give up any of these, you must be improving their life.

The smallest unit of evidence that I consider meaningful is a click. Clicking on a landing page CTA gets 20 points. A click is an expression of intent.

The reason that we click on something is that there’s perceived value.

We know that clicks don’t always translate into a sale. Nonetheless, it’s a good early read on your top of funnel metrics.

Next, email addresses. A personal email address is worth 30 points and a work email address 40 points.

We’re becoming more guarded with giving out our email addresses. I’m finding that people guard their work email address more closely than personal email.

Handing over a mobile phone number is 50 points. We’re more protective of handing over our mobile phone than an email address.

I’m also going to include signing up to a waiting list as 50 points. There’s a stronger level of interest evident if people are willing to sign up for launch day or beta release.

There’s the example of Dropbox securing 75,000 signups in 24 hours after releasing their explainer video.

Referring a product or service to a friend or colleague holds a weighting of 60 points.

We place a much higher emphasis on our reputation, than personal information. If we’re willing to refer a product or service, then it must be considered valuable.

Attracting a prospective customer to a demo, briefing session or in-depth interview is worth 70 points.

Everyone places a high premium on their time. We don’t readily give up our time for activities that aren’t worthwhile.

Getting customers to sacrifice a time commitment for your new product or service is a positive sign.

Top of the leaderboard

The top of the customer evidence leaderboard:

Letter of Intent (LOI) / Signed contract

Free product trial

Deposit / Pre-order

Payment

For B2B transactions, it can be a little more challenging to get skin in the game, particularly for large enterprise customers.

These transactions are often supported by a lengthy sales process that is led by a sales team or account manager.

A Letter of Intent can be a good way to get some skin in the game from a large corporate customer.

A signed Letter of Intent is worth 70 points.

Alternatively, many customers are seeking to try before they buy, enterprise customers included.

I award 80 points for a customer that signs up to your free product and is actively using the value creating features of your product.

Finally, at the end of the day, “cash is king”.

The strongest form of evidence from a customer is always the commitment to pay. Money is the ultimate form of skin in the game.

I award 90 points for a customer that signs up to a pre-order or provides a deposit.

100 points is awarded for a customer that completes a one-time upfront payment or signs up to a reoccurring subscription payment.

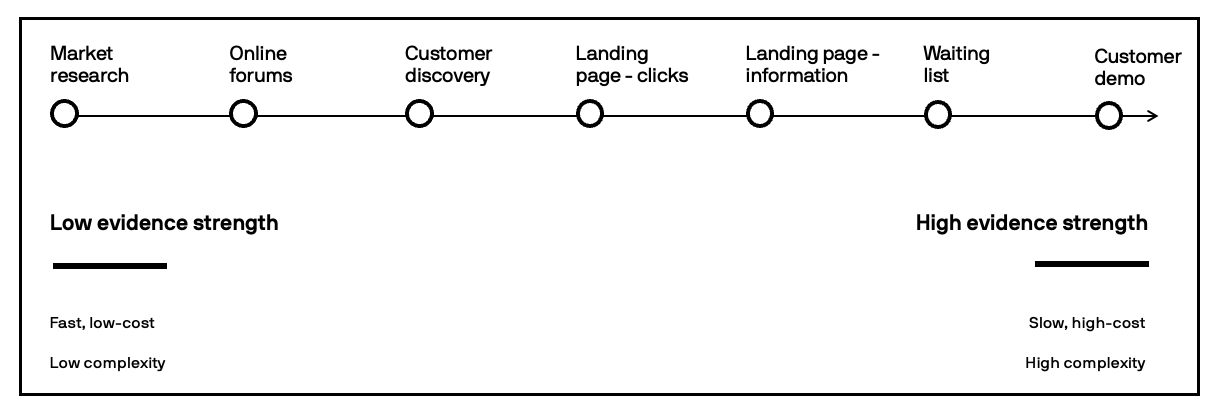

4. Sequence experiments to decrease risk

Sequence experiments over time to decrease risk

Your key objective is to progressively increase customer commitment over time to decrease risk and uncertainty.

I’ve previously written a more detailed blog post on this topic.

The more confidence you generate in your idea, the more you should look to keep increasing skin in the game from your customers.

You don’t need to build a fully-fledged solution to test your hypotheses and riskiest assumptions.

Experimentation is the way that you decrease risk and uncertainty over time.

Experimentation helps you move from a position of low confidence and low evidence strength, to a position of higher confidence and high evidence strength.

A good way to think about testing customer demand for your idea is like a narrative, or story.

A good story has the following attributes:

A beginning

A middle

An end

The beginning

In the beginning, you really don’t know anything about the quality of your idea.

You want to gather evidence and data as soon as possible to commence testing your hypothesis.

Start the process by gathering fast and low-cost forms of evidence – search trends data, customer discovery interviews, forums/discussion boards etc.

What you’re after here is directionality. Are you headed in the right direction or not?

Is my working theory supported or rejected?

You can afford to start out with lower forms of customer evidence strength as, if you’re still on the right path, you can generate stronger evidence later.

The middle

In the middle of the story, we want to start amplifying the strength and quality of the data that you’re getting from your customers.

This will involve running disciplined and targeted experiments to test customer demand and interest in your proposition.

You’re also starting to get sharper on value drivers so that you can better understand how customers interact and behave with your new offering, what they value and what’s important to them.

Some fast, low-cost experiments that you could execute include – email campaigns, Google AdWords campaigns, Facebook Ads campaigns.

You’re trying to drive traffic to a landing page so that you can start to quantify customer demand and early levels of customer interest.

Skin in the game from prospective customers is your goal – clicks, an email address, personal information, or a time commitment.

The end

If you’ve reached the end of the story, you’re still seeing positive indicators and customer interest. This is a good sign.

Customers are interested in your offer. Your solution solves a problem for the customer.

At this stage, you’re looking to use experiments that provide the strongest evidence possible.

These types of experiments are typically the most sophisticated, more costly and can take longer to execute – Concierge, Wizard of Oz, Mechanical Turk.

The strongest form of evidence from a customer is always a commitment to pay.

Aim to capture a deposit or upfront payment. For B2B, try to obtain a signed contract, letter of intent or free product trial.

5. Nomad List - Testing a new online course offer

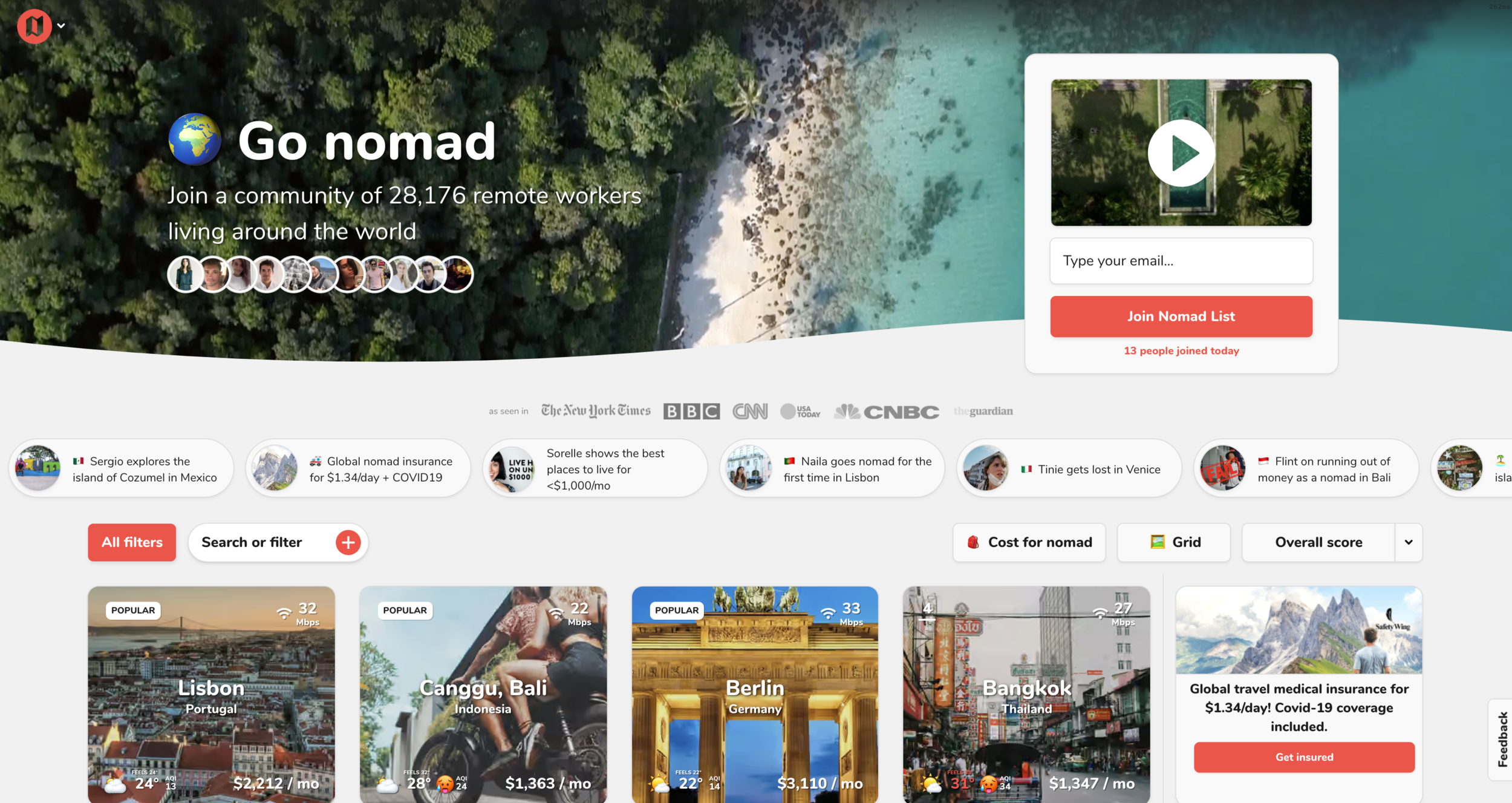

What is Nomad List?

Nomad List started out for digital nomads, but as remote work has become more prevalent, its evolved into a platform for remote workers living anywhere in the world.

Nomad List enables 28,000+ users to find the best places in the world to live, work and travel as a remote worker. Users can access the platform through a paid subscription.

The platform collects millions of data points on thousands of cities around the world, from cost of living, temperature, internet speed and safety. With that data, Nomad List gives users an idea of where it's best to go for remote work, based on their preferences. Each city is provided a unique weighted “Nomad Score”.

In the last 12 months 1,000,000+ people have used Nomad List to find 1,354 cities in 195 countries to live and work.

Testing the proposition

The team at Nomad List were seeking to understand if users were interested in purchasing a new training course offering. Existing traffic to the Nomad List website was used to test customer interest in the new course offering.

The team used Fake Door experiments to measure interest in the new offer.

A series of different price points were tested to understand the optimal price point for the new offer. Monthly revenue was estimated based on the level of customer demand at each respective price point.

“I really like this way of testing. It’s all data based and you know almost exactly what revenue you can expect before creating a new product” - @levelsio

If you have the traffic of an existing product, you can test any new product idea.

The Fake Door experiment

The premise behind the Fake Door experiment is to measure the initial levels of customer demand in your new product, service or feature by putting up a fake entry point (front door).

The experience give the impression that the offer exists, however, the product or service is not available yet.

Traffic is driven to a landing page or website from some type of advertisement where target customers are presented with the offer. The number of customers that “knock” on your front door (click on the CTA) is measured.

The click through rate is measured against the success metrics outlined in your hypothesis.

Nomad List had key three objectives for these experiments:

Test customer demand at a range of price points

Test customer commitment to pay

Estimate monthly revenue at each price point

The lead funnel for these experiments was:

Front Page Banner >

Landing/Sales Page >

Checkout Page

A range of different price points were tested - $29, $79, $99, $119, $139, $249, $449, $849 and $1,299

Every click and page view on the Sales/Landing Pages were measured to understand what price point was optimal.

After clicking through from the Sales/Landing Page customers were taken to a Checkout Page where they enter their credit card details.

The experiment was terminated at this point, with the customer credit card being validated, but not charged.

“It's important it's a real looking checkout page and you actually check if the CC is valid, to be sure that it WOULD be a sale in case it was a real checkout and real product.

After clicking Buy the user is alerted that they're part of a test and their CC isn't charged or saved” - @levelsio

What did we learn?

54 people out of 45,525 website visitors purchased the online course offering.

Interesting that someone was willing to pay $1,299 for the course!

It appears that the sweet spot for pricing sits somewhere between $29 and $119, resulting in monthly revenue of between $5,000 to $10,000.

Exploring further

This experiment has me asking a whole lot more questions.

There’s other areas that I’d certainly like to probe more deeply.

Customer Discovery

After Nomad List initially tested for indicators of customer demand, it would have been interesting to run the same preliminary experiments again, next time capturing personal information - minimum an email address.

From the outside looking in, it appears that Nomad List jumped from the bottom of the customer evidence leaderboard (Clicks - 20 points), to the top (Customer Payment - 100 points).

The risk in doing this is that it can result in missed learning opportunities along the way. It doesn’t help you understand the “why”.

To keep running with the story analogy, it’s a bit like reading the first chapter of a book, then skipping through the rest of the book to the final chapter. You know what happened in the end, but you’ve missed out building context and understanding along the way. The story just doesn’t make as much sense.

I’m not being critical here. Just making an observation.

It would have been invaluable to conduct some Customer Discovery activity to further understand value drivers, needs, problems, pain and JTBD.

These qualitative insights could have then been worked back into the offer, iteratively evolving the proposition, prior to driving customers to hand over a credit card payment.

Conversion rates for the paid offer could have been higher.

Offer Framing

There seems to be an implicit assumption that price is the only lever that is driving customer conversions.

It would have also been interesting to explore some different variations of the offer.

Which offer framing drove the highest conversion rates? Which combination of offer framing and price drove the highest conversion rates?

Customer segmentation

Lots of questions and stuff to unpack here.

Who is the ideal customer? Who were the 54 people that “purchased” the course? What were the characteristics of these customers? What does an analysis of customer segments reveal? Why did these people “purchase” the course? What problem does the course solve for digital nomads? What customer jobs are they trying to achieve?

Also …

Who is the person that “paid” $1,299 for the course? Why were they willing to pay that much? What was the perceived value that they saw in the course? Can you find more customers like this customer? What problem/JTBD are evident for this customer?

Also …

Who were the people that entered the checkout process but didn’t complete the transaction? Why did they abort the checkout process? What would have made them complete the checkout process?

etc. etc.

Conclusion

In the beginning, you have no idea about the quality of your idea.

Anyone will tell you your idea is good enough if you are persistent enough.

Early-stage product development is all about balancing risk and confidence.

The way that you gather data and facts to validate your early hypotheses and riskiest assumptions is with experiments. This helps you to decrease the level of uncertainty and risk over time.

Experiments should be highly targeted, fast, low-cost, and short duration.

Commitment from your early adopter customers demonstrates broad interest, appeal, and commitment in your new product. Customer commitment may include money, time, personal information, or attention.

With appropriate levels of commitment, it warrants an incremental investment in time and money.

You can have more confidence your headed in the right direction.

Highly relevant data from customers always wins out over opinions.

Target customers who are unwilling to put any skin in the game are just spectators.

Need help with your next experiment?

Whether you’ve never run an experiment before, or you’ve run hundreds, I’m passionate about coaching people to run more effective experiments.

Are you struggling with experimentation in any way?

Let’s talk, and I’ll help you.

References:

Before you finish...

Did you find this article helpful? Before you go, it would be great if you could help us by completing the actions below.

By joining the First Principles community, you’ll never miss an article.

Help make our longform articles stronger. It only takes a minute to complete the NPS survey for this article. Your feedback helps me make each article better.

Or share this article by simply copy and pasting the URL from your browser.